|

| Antique Copying Machines |

Antique Copying Machines

Left: Victoria copying machine, Le Bureau Moderne, 1913.

Right: Minolta's update on copying machine advertising imagery.

Second image courtesy of the Museum of Business

History and Technology

Offices need more than one copy of a document in a number of situations. Typically they need a copy of outgoing correspondence for their records. Sometimes they want to circulate copies of documents they create to several interested parties. They may need hundreds of copies of circulars and form letters. During the final quarter of the 19th century numerous competing technologies were introduced to meet such needs. Indeed, one article at the time was entitled “Still Another Letter-Copying Process.” (Manufacturer and Builder, Feb. 1880) The technologies that were most commonly used in 1895 to make copies of outgoing letters and of circulars and form letters are identified in a description of the New York Business College's course program: "All important letters or documents are copied in a letter-book or carbon copies [are] made, and instruction is also given in the use of the mimeograph and other labor-saving office devices." (The Stenographer, July 1895, p. 6) With the invention of copying machines the steps to starting a business (and operating a business) were greatly reduced and made much more efficient.

Copying Clerks

Before the 20th century, correspondence was

principally by hand with pen and ink. Indeed, heavy reliance on calligraphy continued in

offices for decades after the first practical typewriter was marketed by Remington in

1874.

Until the late 18th

century, if an office wanted to keep a copy of an outgoing letter, a clerk had to write

out the copy by hand. This technology continued to be important through most of the

nineteenth century. Offices employed copy clerks, also known as copyists,

scribes, and

scriveners, men who typically stood, or sat on high

stools, while working at tall slant-top desks. Charles Dickens immortalized one such

clerk, Bob Cratchit: “The door of Scrooge’s counting-house was open that he

might keep his eye upon his clerk, who in a dismal little cell beyond, a sort of tank, was

copying letters. Scrooge had a very small fire, but the clerk’s fire was so very much

smaller that it looked like one coal." (A Christmas Carol, 1843. The image of this scene to the right is from 1893.) Herman Melville's story Bartleby (1853)

concerns a lawyer in New York City who employed three male scriveners to copy

testimony and other documents. JoAnne Yates reports that "the Du Pont Company

continued to use hand copy books through at least 1857." (Control through Communications, 1989, p. 206)

Copying Machines Used to Make One or a Few Copies of

New Documents, | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Letter Copying Presses |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Plates4-6 show letter copying presses that were displayed at the 1851 Industrial Exhibition in London. Along with typewriters, letter copying presses are the most common machines found in photographs of late 19th century and very early 20th century offices. Yates (Ch. 4-5) reports that the Illinois Central Railroad used copying presses to make copies of outgoing letters in press books at least from the late 1850s to 1896, that the Repauno Chemical Co. stopped using press books in 1901 (p. 226), that the Scoville Manufacturing Co. was still using copy presses and press books for outgoing letters in 1913 (p. 181), and that the Hagley Museum and Library has press books that were used in the 1930s (p. 283). The last U.S. President whose official correspondence was copied on a copying press was Calvin Coolidge (1923-29). (David Owen, "Making Copies," Smithsonian, Aug. 2004, p. 92) Screw model letter copying presses were still marketed in 1950, and Proudfoot reports that an organization in London, England, was still using press books in the late 1950s. (W. B. Proudfoot, The Origin of Stencil Duplicating, 1972, p. 32) Because of the size and weight of letter copying presses, numerous portable methods for pressing loose copies and copy books were also marketed during the 19th century. In a review of office equipment at the 1851 Industrial Exhibition, Granville Sharp recommended that when an office was selecting a press like those in Plates 1-3, it should make sure that the handle was heavily weighted at the ends to insure proper spinning. “This is essential to a screw copy press; for unless one pull will serve to raise or to depress the plate, much time is lost.” In addition to the press, offices needed to buy copying books that contained up to a thousand pages of tough tissue paper, copying ink, copying paper dampers, oiled paper, and blotting paper. Sharp explained that before using the new press, the office had to decide how to organize its letters. Production of copies was easiest if the user copied its letters into a single letter book in chronological order. In that case, the user needed to make an index so that letters of interest could later be retrieved. Alternatively, the office could organize its correspondence by client, which avoided indexing but made it necessary to use numerous copying books on a given day. Although copies could be made up to twenty-four hours after a letter was written, copies made within a few hours were best. A copying clerk would begin by counting the number of letters to be written during the next few hours and by preparing the copying book. Suppose the clerk wanted to copy 20 one-page letters. In that case, he (copying clerks were men) would insert a sheet of oiled paper into the copying book in front of the first tissue on which he wanted to make a copy of a letter. He would then turn 20 sheets of tissue paper and insert a second oiled paper. Sharp advised that “Success in copying letters depends almost entirely upon the damping of the paper. The paper should be saturated and damp, not wet.” To dampen the tissue paper, the clerk used a brush or copying paper damper. The damper had a reservoir for water that wet a cloth, and the clerk wiped the cloth over the tissues on which copies were to be made. (See Plate 5A) As an alternative method of dampening the tissue paper, in 1860 Cutter, Tower & Co., Boston, advertised Lynch's patent paper moistener (Plate 5B) with the claim that "it does away with the use of the brush, wet cloths and dipping bowls, and dampens the paper sufficiently by a single roll of the machine." Next, letters were written with special copying ink, which was not blotted. The copying clerk arranged the portion of the letter book to be used in the following sequence starting from the front: a sheet of oiled paper, then a sheet of letter book tissue, then a letter placed face up against the back of the tissue on which the copy was to be made, then another oiled paper,et cetera, “oiled paper being in all cases placed next the damp paper, to prevent the ink forcing beyond the paper intended to receive it.” Finally, “Close the book, put it into the press, and screw tightly down, letting it remain a minute or two under pressure, when the copy will be properly taken, and may be dried with blotting paper, or held near the fire.” Based on experience, the clerk could adjust the press time. If he made a copy soon after a letter was written, only a second or two was needed to make a good impression. When the letter book was pressed, some of the ink transferred from the letters to the moist tissues in the book. Because the ink penetrated the tissues, copies could be read from the front sides of the tissues. Prior

to the introduction of inks made with aniline dyes, the quality of copies made on letter

copying presses was limited by the properties of the available copying inks. The

first aniline dye was invented in 1856, and numerous aniline dyes were

invented in the following two decades. Bedini (p. 193) reports that "The growth of the aniline dye and ink

manufacturing industries in Germany, which coincided with the earliest

importation in 1868 of thin papers manufactured in Japan, brought a new

popularity to the bound letter book."

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Copying Pad Baths

By the late 1870s, an improved method for moistening pages in

copying books had been invented, and by the late 1880s it had been widely adopted. Rather than using a brush or damper to wet the tissues,

the clerk inserted a thin moist cloth or pad between each oil paper and the following

tissue. A supply of moist pads was prepared in advance using a copying bath,

such as Hill's Blotter Bath, patented in 1879 (Plate 6B), or Tatum's Ideal Copying Pad Bath, patented in 1887 (Plate 7). Tatum also produced larger

copying tanks that included wringers to remove excess water from copying

pads. The Globe Roller Copying Bath (Plate

8), which

was marketed by Globe-Wernicke Co. in the early 1900s, is an example of a

copying tank. To

prepare a supply of moist pads using the Ideal bath, the clerk removed the tray from the

bath, poured water into the pan, and replaced the tray. Also, the clerk sprinkled a set of

pads, let them stand overnight, and then placed them in the tray. “The evaporation

from the water underneath will generally be sufficient to keep pads damp enough for

ordinary work.” Plate 8A shows an 1886 Bailey's Letter Copying

Machine with a Moistening Attachment on top. Plate 8D shows a Little Giant Copying Tank, which was priced at $9. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Copying Books Plate 9 shows a letter copying book with copies of typed letters from 1905. |

Plate 9, Letter Copying Book, 1905 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Portable Copying Presses Plate 10 shows an 1881 advertisement for an Atmospheric Letter Copying Press. The copying book was inserted into a slot on the side of a narrow wooden case. Pressure was then applied to the book by manual inflation of a flat balloon inside the case. Plate 10AA shows an 1889 advertisement for the Jewel Copying Press, which was similar in concept, but pressure was applied by moving a lever. At the 1885 Novelties Exhibition in Philadelphia, Alvah Bushnell exhibited his Perfect Letter Copying Book, which did not use a press.Plate 10A shows an 1895 advertisement for Bushnell's Perfect Letter Copying Books; Plate 10A2 shows the cover of one of these books and instructions. A letter to be copied was placed in the flexible book, which was then rolled up around a wooden rod attached to its spine. "The principle of copying is the same as with a copying press. The covers of our books are flexible, and sufficient pressure is easily given by rolling them up in the hands." "Two thin, tough manila sheets of paper are supplied with each book, to take the place of the stiff oil sheet used with the copying press, and one piece of thin muslin the same size as the leaves of the book is furnished, which, when properly dampened, is used to moisten the leaf when making the copy." In the 1890s, Bushnell's device was $1.00 to $1.60, depending on size. The device as still advertised in 1908. At the same 1885 exhibition, Sagar Chadwick exhibited the Chadwick Copying Book. He claimed that with it one "copies written matter made with ordinary ink by simply laying such matter on a page of the book and rubbing with the hand, dispensing with the use of a press, brush, and bowl." Unlike Bushnell's book, we have found no subsequent mention of Chadwick's. Plate 10B shows a portable Cylindrical Copying Press and cabinet that were marketed by the Portable Copying Press and Stationery Co. in 1888-89. To use the press, one placed a sheet of damp copying paper against an original letter and rolled these around a cylinder. One then inserted this cylinder inside a cylindrical press and applied pressure by turning crank. Another type of portable copying press is shown in Plate 10C, which is from a c. 1920s advertisement in Germany.  Plate 10D, Eclipse Coping Press, Reg No. 38902. Courtesy of Kev

Murray. Plate 10D, Eclipse Coping Press, Reg No. 38902. Courtesy of Kev

Murray. |

Plate 10, Atmospheric Letter Copying Press, 1881 Picture coming [GS 040489] Plate 10AA, Jewel Copying Press, 1889  Plate 10A, Bushnell's Perfect Letter Copying Books, 1895 ad   Plate 10A2, Bushnell's Perfect Letter Copying Book, copyright 1885, cover and instructions. Courtesy of the Museum of Business History and Technology

Image coming | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Roller Copiers |

Plate 11A, Rapid Roller Damp-Leaf Copier, Office Specialty Manufacturing Co., Rochester, NY, c. 1889 ad.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Loose-Leaf Copiers The Process Letter Machine Co., Muncie, IN, offered the New Rotary Copying Press, a loose-leaf copier, in 1902. This machine was similar to roller copiers but copied onto loose-leaf paper. The Cylinder Letter Press Co., Chicago, IL, and The Easy Machine Co., Marion, IN, offered different loose-leaf copier, the Cylinder Letter Press and the Quick Easy Copying Press, respectively, in 1903 and 1905, respectively.  Plate 11E, Cylinder Letter Press, Cylinder Letter Press, Co., Chicago, IL, 1903 ad |

Plate 11C, The New Rotary Copying Press, 1902 ad  Plate 11D, Quick Easy Copying Press, 1905 illustration | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polygraphs A polygraph is a mechanical device that moves a second pen parallel to one held by a writer, enabling the writer to make a duplicate of a document as it is written. Although polygraphs in the 17th century, polygraphs did not became popular until 1800. Hawkins & Peale patented a polygraph in the US in 1803, and beginning in 1804 Thomas Jefferson collaborated with them in working on improvements in the machine. Jefferson used a polygraph for the rest of his life. However, polygraphs were not practical for most office purposes and were never widely used in businesses. Hawkins & Peale lost money producing polygraphs. One problem was their "inherent instability, and constant need for repair and adjustment." (Bedini, p. 187) Plates 12-12A show polygraphs owned by Jefferson. For additional photographs of Jefferson's polygraphs, click on the following two links to the Library of Congress (1,2). |

Plate 12, Polygraph 1803  Plate 12A, Polygraph 1803, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, on loan from the Franklin Institute | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Carbon Paper, Manifold Books and Typewriters Nevertheless, use of carbon paper was modest until the 1870s. Early carbon paper was messy, carbon paper did not make a satisfactory copy when the original was written with a pen, there was concern that carbon copies could be altered or forged, and carbon copies were not admissible in court. Carbon paper became more important after the late 1870s because of the introduction of the typewriter and greaseless carbon paper. Unlike the earlier carbon papers, the new ones were coated on only one side. Typewriters were able to produce up to ten carbon copies along with an original. Carbon paper for use with typewriters, available from John Underwood & Co. among others, was advertised in 1886 (A.C. Farley & Co., The Purchaser, Philadelphia, PA, Feb. 1886. Hagley Museum and Library). Yates reports that in 1912 a government report stated that "by the almost universal practice of business concerns, the carbon copy has supplanted the press copy as a record of outgoing correspondence." According to Yates (p. 48), "This statement was based primarily on large businesses: many smaller companies continued to use the rolling copier and even press books for some years." |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Machines Used to Make Many Duplicates | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Printing Presses Neither letter copying presses nor carbon paper could be used to make numerous copies of a document. Until the mid-1870s, offices had two options for making many copies. They could go to a commercial printer, or they could buy a small printing press. In the 19th century, commercial printers used platen presses for job work such as business cards, envelopes, billheads, and circulars. (Harold E. Sterne, Catalogue of Nineteenth Century Printing Presses, 1978, p. 217) Yates (Ch. 4) indicates that until 1876 the Illinois Central Railroad used commercial printers when it needed large numbers of copies of items such as circulars, and that it continued to use commercial printers after 1876 when it needed multiple copies of documents to be distributed to the public rather than for internal use.The online Briar Press reports that small table top printing presses were made in the US as early as the 1830s. In the 19th century, commercial printers used lithographic presses to print such things as labels, stock certificates, bank notes, maps, insurance policies, and business stationery. Sterne (p. 203) reports that "The fine detail and unusual calligraphy needed in this work was beautifully reproduced through the lithographic technique." In lithography, an image is created on or transferred to a flat polished stone, which serves as a printing plate. The image is created on the stone using a greasy crayon, or alternatively is created on a sheet of paper using greasy lithographic ink and then transferred to the stone. Next, printers ink is applied to the stone. This ink adheres only to the crayon or lithographic ink. The stone is then covered with a sheet of paper, and the stone and paper are run through a press to make a lithograph. In England, small lithographic

presses were marketed to offices in the 1850s. One example that was

exhibited in 1851 is the S. Mordan & Co. Combined Lithographic and Copying Press (Plate

14). To use this as a

lithographic press, it was necessary to transfer a document image

to a smooth limestone block. A second example that was exhibited in

1855 and described as suitable "for

the Counting House, Office, or Library" was exhibited by Waterlow and

Son of London in 1855 (Plate 14AAA). Waterlow's advertisement

stated: "Nearly One Thousand of these Presses have now been sold, and

are being successfully used in all Her Majesty's Government Offices,

Public and Private Schools, Railway Companies, Assurance Offices, and also

by the most influential Bankers, Merchants, Clergymen, &c., in the

United Kingdom." The available evidence suggests that such

lithographic presses were not used widely, if at all, in offices in the US. William Tuttle and Benjamin O. Woods produced small lever presses in Boston, MA, by 1857. A lever press is a table-top hand-operated version of the larger foot-operated platen press used by commercial printers. Woods advertised small Novelty printing presses in 1870 and exhibited them at the Centennial Exhibition in 1876. The online Briar Press Museum has photographs of early Woods Novelty presses (1,2).

Small lever presses were sold in a wide range of sizes by

numerous companies. Lever presses that printed items measuring 1.5" x

2.5" were as little as $2 while larger ones with the capacity to

print items as large as 11" x 16" were as much as $160. |

Plate 14, Mordan Co. Press, 1851

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Stencil Duplicating Machines |

Add image from Scientific American May 25, 1872. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Papyrograph In 1874, Zuccato obtained a US patent for the first commercially successful stencil copying process for use in offices. His Papyrograph process began with a sheet of lacquer-coated stencil paper that could not be penetrated by liquid. By writing on this stencil with corrosive ink, a clerk made the affected parts of the stencil porous so that liquid would pass through. An improved version of the Papyrograph system that was patented in 1876 and marketed by 1877 by the Papyrograph Co. of Norwich, CT, used a horizontal sliding frame that was twice the width of the printing surface of a letter copying press. The operator placed this sliding frame so that half covered the printing surface of a letter copying press and the other half was next to the press. The operator then placed an inked pad on the half of the sliding frame that was next to the press, placed a prepared stencil face down on the inked pad, and covered the stencil with a sheet of paper. The operator then slid this "sandwich" inside the copying press and lowered the press to make a copy. The manufacturer claimed that "By this process from 300 to 1000 facsimile impressions can be taken upon Dry and Unprepared Paper, direct from the original writing, in an ordinary Letter-Copying Press." The supplier claimed that 5,000 Papyrographs were in use in the US in June 1877. Although advertisements claimed an operator could make 400-500 copies per hour, the method was slow and messy. Also, the stencils could not be prepared with a typewriter. Nevertheless, the Papyrograph was advertised as late as 1885, with the claim that "Thousands are now in use in the United States and foreign countries." In 1878, a complete Papyrograph system, including press and supplies, was $23 to $75. |

Plate 14C, Zuccato's Papyrograph, The Papyrograph Co., Norwich, CT, 1878 a | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Edison Electric Pen In 1875, Thomas Edison and Charles Batchelor developed a stencil system for copying handwritten documents, Edison’s Autographic Press and Electric Pen. The operator would hold a special pen (Plate 15) in a vertical position and write or draw on a stencil resting on a sheet of blotting paper. The pen was 5 ¾” tall and top-heavy. The top portion was a small uncovered electric motor attached by flexible wires to a nearby two-cup wet battery containing water and sulfuric acid (Plate 16). Each time the motor’s horizontal shaft rotated, a cam attached to the shaft caused a needle inside the pen to make three vertical strokes, each one cutting a minute hole in the stencil. The pen made approximately 135 perforations a second. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

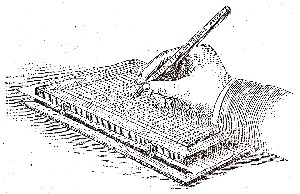

| Edison’s

1876 patent explains that to print copies one placed the stencil over the paper

on which an impression was to be made. A felt-covered roller was used to press

ink through the perforations in the stencil to the surface of the sheet below.

The patent describes a simple hand press consisting of a flat bed with a hinged

frame to which the stencil was attached. Presses are shown in Plates 17-18. A

contemporary account stated that copies could be produced at the rate of 4 to 5

per minute, and that a stencil could be used to produce 1000 copies. Faster

printing presses were patented by others. According to an 1881 account, "Henry

S. Norse has patented an improved duplicating press. The object of this

invention is to furnish a foot or power press for use in printing from stencil

plates, particularly stencils prepared with the Edison electric pen, so that the

labor and time heretofore required in such work shall be reduced."

(Scientific American, May 14, 1881)

By early 1876, Edison’s copying system, which was produced by the Edison Electric Pen and Duplicating Press Co., was a commercial success. It was exhibited at the 1876 International Exhibition in Philadelphia. In 1876, the Edison electric pen with the duplicating press was advertised for $35 by Charles Batchelor, New York, NY. (Publishers' Weekly, Vol. 10, 1876, p. 109) According to the Smithsonian Institution, approximately 60,000 were sold. However, sales were constrained by the fact that many office clerks did not have the skill or motivation to maintain the complicated battery. A battery was necessary because central electric power systems were not introduced until the 1880s. Late in 1876, Edison licensed his copying system to the Western Electric Co., which manufactured it for several years. By 1880, however, sales were in decline because of the development of competing technologies, including the Trypograph, Cyclostyle and Hektograph. There were, however, some people who preferred the Edison system. According to an 1885 testimonial, "It may be of interest for one who has used the papyrograph and the hektograph, but with no great satisfaction, to state that every other system always drives me back to Edison's electric pen as the neatest, readiest, and in every way the most satisfactory copying system. An experience of eight years with it has always been very satisfactory." (Christian Union, June 4, 1885) A number

of other companies marketed similar systems, including some with pneumatic

perforating pens driver by foot-powered bellows. According to one contemporary

account, "a pulsating pen, driven by the foot like a sewing machine, rivals the

Edison electric pen. It is certainly lighter to write with, and requires no

battery, with its acids, to spoil clothing. This is on show by Ward &

Drummond." (Christian Union, Oct. 29, 1879) According to an 1885 trade press discussion referring to the Edison electric pen, "Other perforating pens working pretty much upon the same principle, with the exception that the motive power is supplied by clockwork, have made their appearance in England....while a far more expensive and complicated method consisted of an induction coil which can produce a spark of sufficient power to perforate paper, which is made to pass continually between a pen of metal partially insulated and a metallic plate upon which is laid the perforated paper." (Geyer's Stationer, 1885)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trypograph In 1877, Zuccato introduced the Trypograph, which used an alternative method for producing stencils. A wax-covered stencil was placed on a metal plate with a file-like surface with thousands of perforating points. When a metal stylus was used to write on the stencil, the stencil was perforated from below by the file. A similar method is illustrated in an 1880 patent awarded to Edison (Plate 19A). Trypographs were still sold at the end of the 19th century. |

Plate 19, Trypograph marketed by Zuccato & Wolff, London  Plate 19A, Edison Stencil Perforation 1880 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

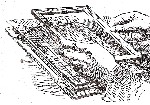

| Cyclostyle In 1881, David Gestetner patented the Cyclostyle wheel pen, which was superior to Edison’s electric pen because this wheel pen did not require a battery and produced better stencils. On the tip of the Cyclostyle pen was a minute steel wheel with a toothed edge. As the pen was moved over a wax-covered stencil, the teeth perforated the stencil. An improved version was named the Neo-Cyclostyle or Neostyle wheel pen. See Image 1 to the right. Advertising for and sales of the Cyclostyle began in 1884. According to an 1884 product review, "This apparatus consists of a hard metallic surface fitted into a frame of polished walnut, over and above which is fitted a similar frame of walnut." To use the apparatus to make copies, the top frame is unhooked and removed, and an unused Cyclostyle stencil is placed on the metal surface. "The top frame is then replaced." See Image 2 to the right. "The matter to be copied is next written upon the [stencil] with the cyclostyle pen." See Image 3 to the right. "The upper frame [including the stencil] is then raised, and a piece of paper is placed upon the metallic plate." See Image 4 to the right. "The roller, having received an evenly distributed layer of Cyclostyle ink, is then passed [by hand] over the writing [on the stencil] to be copied." This forces ink through the stencil and onto the paper, making a copy. See Image 5 to the right. "The frame is then raised, the printed copy [see Image 6 to the right] is removed, fresh paper [is] placed upon the surface, and this same process [is] repeated until the desired number of copies has been obtained." It was claimed that copies could be made at the rate of 400 per hour. (Geyer's Stationer, 1884-85) Manual Cyclostyle, Neo-Cyclostyle and Neostyle copying systems were sold from 1884 until the late 1890s, and possibly longer, in boxes similar to the Edison Mimeograph (see Plates 22 and 23). In 1887, boxed Cyclostyles were $12.50 to $22.50, depending on size. |

Image 1, Neostyle Wheel Pen, 1888  Image 2, Cyclostyle, 1884  Image 3, Cyclostyle, 1885  Image 4, Cyclostyle 1884  Image 5, Cyclostyle, 1884  Image 6, Cyclostyle, 1884 Stygmograph

|

The Stygmograph (Plate 21A) was advertised in 1884 as a copying pen for writing by hand on duplicating stencils.  Plate 21A, Stygmograph, 1884 Mimeograph |

Albert Blake Dick invented the Mimeograph stencil in 1884. The A. B. Dick Co., Chicago, acquired Edison’s copying system patents and, with Edison’s support, began manufacturing and marketing Edison Mimeograph systems in 1887. Models were sold in rectangular wooden boxes (Plates 21B-23). The boxes contained a hand printing frame that consisted of a flat bed or printing board and a hinged frame that held the stencil. The boxes also contained an ink roller, an inking slate, ink, varnish and a brush for making corrections, waxed stencil paper, blotters, a writing stylus, and a writing plate with a file-like surface (see Plate 19) that was 1.5" to 3" top-to-bottom and as wide as the printing frame. To prepare a handwritten stencil, "A sheet of Mimeograph stencil paper is placed over the finely grooved steel plate and written upon with a smooth pointed steel stylus, and in the line of the writing so made, the stencil paper will be perforated from the under side with minute holes, in such close proximity to each other that the dividing fibers of paper are scarcely perceptible." After the operator has written a few lines, the operator moves the stencil upward over the writing plate so that a new portion of the stencil is on top of the writing plate. "After the stencil is completed it is placed in the printing frame, by which the stencil is firmly held taut and in a position for rapid printing. After inking the roller on the slate furnished for that purpose, pass it over the stencil sheet and a correct reproduction of the matter stenciled will appear on the paper which has been previously placed underneath." Ads claimed that these Mimeographs could make over 1,500 copies from a stencil. A. B. Dick claimed to have sold over 80,000 Edison Mimeographs by 1892 and over 200,000 by 1899. In 1889, Mimeographs were $12-$29.50, depending on size and whether they included the items needed for handwritten, typewritten, or both types of stencils. Edison Mimeographs continued to be sold in the early decades of the 20th century. The model numbers denote different sizes and features. In 1889, the models used for handwritten stencils were identified as No. 0 to No. 5; the model for typewritten stencils only was No. 12; the models for both types of stencils were No. 20 to No. 25.

|

Stencils Cut with a Typewriter |

Until the late-1880s, stencils were written by hand. The types of stencils that had been developed could not be prepared by typewriters. Typewriter stencils were introduced in the late-1880s and underwent significant improvements during the following years. One way to cut a stencil with a typewriter was to cover the stencil with a fine "perforating silk" cloth and type without a ribbon. In 1894, the A. B. Dick Company marketed the Edison Mimeograph Typewriter shown in Plate 24 (with the carriage raised); for additional photographs, click here. For a discussion of the Edison Mimeograph Typewriter, go to the Museum's exhibit on Antique Office Typewriters.  Plate 24, Edison Mimeograph Typewriter 1894 Automatic

Stencil Duplicators |

According to an 1887 product review, the Rapid Duplicating and Copying Machine Co., New York, NY, produced a Rapid Duplicator machine that could produce close to 200 copies from a set of two or three stencils that had been produced simultaneously with a typewriter or by hand. The Rapid Duplicator is illustrated in the top image to the right. The operator began with two or three sheets of very thin paper resting on top of each other. Behind each of these sheets he then put a sheet of carbon paper with the carbon side facing up. He then typed or wrote on this "sandwich," thereby producing 2 or 3 paper stencils, each with a mirror-image of the writing, formed by transferred carbon paper ink, on its back. Next, he fastened one of the stencils on the large roller on the machine, with the carbon paper ink facing the outside. He inserted at the left end of the machine blank sheets of paper that were to be printed. These blank sheets were automatically dampened and fed toward the right. A special roller squeezed excess moisture out of the dampened sheets. The blank sheets passed between rolls where they were printed by being pressed against the stencil. The printed sheets exited at the right end of the machine. If three stencils were made, the first was able to print around 75 sheets, the second between 50 and 75 sheets, and the third around 50 sheets. In 1894, Gestetner introduced the first "automatic" stencil duplicating press, which was sold as the Automatic Cyclostyle until 1900. An illustrated 1899 advertisement is reproduced to the right. (See second image from top.) The machine had three rollers. The operator squeezed ink from a tube onto the middle roller. The top roller spread an even coat of ink over the middle roller, which transferred an even coat of ink to the bottom roller. The bottom roller transferred ink through the stencil to the paper that was being printed. The automated features of this apparatus were the inking of the bottom roller and the movement of the inked bottom roller over the stencil. Paper was still fed into the machine manually and printed copies were still removed manually, one sheet at a time. According to a trade press discussion of this machine, a person wishing to make a number of copies used a Neo-Cyclostyle pen or a typewriter to make a stencil. The machine operator put the stencil into a frame mounted horizontally on the bed of the machine. The operator then turned the handle on the press alternately left and right. This caused the bed of the machine to slide back and forth under the rollers. (1) When the bed went to its limit in the first direction, the frame opened and the operator placed a new sheet of paper under the stencil. This is what you see in the 1899 ad to the right. (2) The operator then turned the handle. The frame closed, the bottom roller rose so that it touched the top roller, and the bottom roller was inked by the top roller while the bed slid back under the rollers in the second direction. (3) The operator then turned the handle in the reverse direction. As the bed with the frame passed under the rollers in the first direction, ink was pressed through the stencil by the bottom roller and a copy was made. (4) When the bed went to its limit in the first direction, the frame opened. The operator removed the copy. Now we are back to (1): the operator placed a new sheet of paper under the stencil, and the process was repeated. It was claimed that one inking of the middle roller was sufficient for 100 to 200 copies, and that 2,000 copies could be made from a stencil. (Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society, Annual Report, 1894) In addition to the printing frame sold in the wooden box (Plate 19), in the 1890s A. B. Dick sold metal Mimeograph presses (Plate 26). In 1896, the Neostyle Co. marketed the Automatic Neostyle with the claim that "The machine is automatic in the full meaning of the word--the printing is automatic, the frame is opened and closed automatically, the pressure of roller is automatic, the distribution of ink is automatic, the copies are discharged as fast as printed automatically, the number of copies printed is automatically recorded, the ink is supplied automatically." These automatic presses speeded the duplicating process. Plate 26, Mimeograph Presses 1896 In 1895, Stackhouse & Krumbhaar, Philadelphia, PA, advertised the Diagraph Stencil Printing Machine, which was described as "The only perfected, automatic and rapid stencil printing machine." According to an 1898 ad, "Prints from 500 to 3,000. Copies from one original at the rate of 20 to 40 copies per minute. It is a simple, economical, practical device for duplicating circulars, letters, pricelists, etc., in perfect imitation of hand- or typewriting.

|

Rotary Stencil Duplicator |

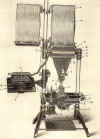

The Neostyle Co. marketed the first rotary stencil duplicator in 1898, further increasing the speed of duplication. In 1899 the Rotary Neostyle was advertised with a choice of hand crank, foot treadle, or electric motor. (Plate 27) Model 8-F 1909 In 1913, the Rotospeed Co., Dayton, OH, advertised a hand-crank rotary stencil duplicator similar to the Rotary Neostyle (upper image to the left). The price was $25. System, Oct. 1913.  Plate 27A, Rotary Neostyle, Neostyle Co., NY, NY, 1898 ad  Plate 27, Rotary Neostyle, electric model, 1899 A. B. Dick

Co. began to sell Edison Rotary Mimeograph systems in 1900. In 1909, A. B. Dick

claimed that the Edison Rotary Mimeograph No. 75 (Plate 30)

could produce 2,000 perfect copies from a stencil at a rate of 45 to 50 copies a

minute. For printing, the prepared stencil was attached to exterior of the

perforated hollow metal drum. As the drum was turned, ink was extruded through

the stencil to sheets of paper fed under the drum. In 1914 Rotary Mimeographs

were $30 to $160, depending on features. A. B. Dick was selling Models 75, 76,

77, 78, the last both manual and electric, in 1930. A. B. Dick continued to use

the Edison name on such systems until 1940. |

Plate 30, Edison Rotary Mimeograph No. 75, 1904

In 1906 the Roneo Co. introduced the Roneo Copier

(Plate 30B), a "dry" copying machine that made copies on a paper roll

impregnated with a glycerin solution that kept the paper uniformly moist for

several months. Copies were made on the roll, which was then cut and dried to

yield individual copies. The 1914 advertisement from Norway shows this same

Roneo Copier (Plate 30B2). The Soennecken copying machine (Plate

30C), which was made in Germany and sold in France as of 1913, appears to

have been similar to the Roneo. |

Plate 30B, Roneo Copier, 1906  Plate 30B2, Office with Roneo Copier, Norway, 1914. Courtesy of Harald Bohne  Plate 30C, Soennecken Copying Machine, 1913 Gestetner

stencil duplicating machines (Plate 31) had two drums instead of the

usual one drum. The stencil was attached to a band around the two

drums. |

Plate 31, Gestetner Rotary Cyclostyle No. 6 Mimeoscope |

In 1914-16, the A. B. Dick Co. patented the mimeoscope (Plate 32). A mimeoscope, which is basically a light table, had an electrically-illuminated glass top on which the operator traced drawings onto mimeograph stencils. The stencil took the place of tracing paper. The electric light was needed because the stencils were heavier and less transparent than tracing paper.   Plate 32, Mimeoscope, patented 1914-16, advertised 1920-30 Hektograph and Spirit Duplicators |

The stencil copying systems described above involved pressing or extruding ink through stencils onto sheets of paper. In the hektograph (also spelled "hectograph") process, which was introduced in 1876 or shortly before, a master was written or typed with a special aniline ink. The master was then placed face down on a tray containing gelatin and pressed gently for a minute or two, with the result that most of the ink transferred to the surface of the gelatin. Gelatin was used because its moisture kept the ink from drying. Copies were made by using a roller to press blank papers onto the gelatin. Each time a copy was made, some ink was removed from the gelatin, and consequently successive copies were progressively lighter. In practice, up to fifty copies could be made from one master. Plate 33 is an 1876 ad for J. R. Holcomb & Co.'s Transfer Tablet hektograph. Plate 33B shows another hektograph, Lawton & Co.’s Simplex Printer, which was introduced by a predecessor company, General Copying Apparatus Co., by 1889. The Simplex was $3 to $29.50, depending on size. Yates (p. 122) reports that "By 1885 the [Illinois Central Railroad] Freight Office's need for a neat alternative to printing had led it to adopt...the hectograph....Using a hectograph in the Freight Office, rather than sending the rate circulars to be printed, was faster as well as cheaper. And although the hectograph duplicating process itself was messy, the final products were neater and more readable than those produced with the Edison Electric Pen." An 1887 ad stated that a hektograph could be used to make 15 to 40 good copies of a letter typed on a Hall index typewriter. Hektograph copiers were still marketed by the Heyer Hektograph Co. (founded 1903) in the 1950s.

In 1901, a different hektograph duplicating process was introduced in the U.S. (W. H. Leffingwell, The Office Appliance Manual, 1926, p. 378.) Rather than using a gelatin pad, this process, which was invented in Germany in 1880 and marketed as the Schapirograph, used a roll of paper coated with gelatin, glue, and glycerin. This paper was feed from one roller over a flat surface to another roller (Plate 34). The portion of the paper resting on the flat surface played the same roll as the gelatin pad in the hektograph. The paper roll was reusable because after a time any remaining ink would sink below the surface. These were advertised as late as 1922. The Commercial Duplicator, advertised by Duplicator Mfg. Co. during 1913-17 (and probably longer), appears to have used a similar technology to produce up to 100 copies of a document "from the original itself" written in duplicator ink. (System, Sept. 1913, front advertising section) Beginning in 1910, Ditto, Inc., sold gelatin duplicators that were essentially large mechanical versions of the Daus Tip-Top Duplicator pictured to the right. The Ditto process could be used for up to 100 copies. Plate 34A is a 1925 Ditto machine. "When preparing the original, hard bond paper and a special kind of ink [containing aniline dyes] are used. This may be in the form of a duplicating typewriter ribbon, a duplicating ink, or even an indelible pencil. The original is placed face down on the copying surface and smoothed with the palm of the hand or a roller. It is then lifted off, having left its impression on the gelatin. The blank sheets are placed one at a time on the gelatin surface and allowed to remain a few seconds until the imprint is made." The Ditto machine in Plate 34A was $200. In 1925, other models were $117 to $395. The spirit duplicator,

which was introduced in 1923 and which was marketed for several decades, evolved

from the hektograph and Ditto machines described above. The best-known spirit

duplicator company was Ditto, Inc. The Ditto process involved the creation of

masters and the transfer of ink from masters to copies. A Ditto carbon consisted

of a sheet of slick, impermeable paper (the master) attached to the front of a

second sheet that had on its face a coating of paste-like ink. When one typed or

drew on the front of the master, a reverse image in heavy ink was transferred to

the back side of the master. The master was then detached from the second sheet

and attached to the drum of a rotary press with the inked surface outward. When

the drum was rotated, the inked surface of the master was wiped with a solvent

such as spirit ether to wet the ink, and until the ink was exhausted impressions

were made on papers that were fed under the drum.  Plate 33, J. R. Holcomb & Co. Transfer Tablet Hektograph, 1876 ad Plate 33B, Lawton Simplex Printer, 1895 ad. The illustration shows three gelatin trays.  Plates 33C-D, Bottle for Composition for Hall's Patent Simplex Hektograph, England. Photo below shows instructions on back of bottle.   Plate 34, Daus Tip-Top Duplicator, advertised 1901. [Picture coming. H] Plate 34A, Ditto Standard No. 2, as of 1925 Ditto Inc.'s most popular model.  Plate 34AA, Model E-41, Ditto Division of Bell & Howell, c. 1950s Cylinder

Duplicators |

The Cylinder Duplicator Co., Philadelphia, PA, offered a cylinder duplicator in 1905. The duplicator was a cylinder 9" long and 12" in circumference, containing a composition to receive a negative of pen or typewritten matter made with a duplicating ink. Duplicate copies were mae by running the roller over blank papers. The maker claimed that the device would make 50 to 75 copies of letters written with a typewriter and 100 to 125 copies of letters written with a pen.  Plate 34B, Cylinder Duplicator, 1905 illustration

|

Lithographic Duplicators In the 1880s, a number of

office duplicators were introduced that used lithographic processes, but the

stone was generally replaced by a zinc plate or even parchment. According to an

1880 description, the process of using Anderson's New Auto-Lithograph "consists

in writing the original document with chemical writing fluid with any pen on

ordinary writing paper, and when dry this original is placed ink-side downward

upon [a sensitive plate], and left for two or three minutes. It is then removed

and a negative impression, in perfect and beautiful relief, will be found on the

plate. The roller having been previously inked with copying ink is now passed

over the negative, and it will be seen that all the lines will have taken the

ink. A sheet of paper being laid upon this impression is smoothed over with the

hand, and on removing it a perfect copy in permanent jet black will be obtained.

This may be repeated for a number of copies, and when they become faint the

impression may be re-inked with the roller and the copies will be as at first.

When the requisite number of copies are taken, the impression may be washed off

with water and a sponge." (Geyer's Stationer, Oct. 7, 1880, p.

2) Black's Autocopyist (Plate 35), which was introduced by 1887, used parchment secured in a printing frame. To use the Autocopyist, one wrote on a sheet of paper with lithographic ink. This paper was then laid face down on the dampened parchment, and pressure was applied to the back of the paper, causing the lithographic ink to transfer to the parchment. Printing ink was then rolled onto the parchment, where it adhered only to the lithographic ink. Next, a sheet of paper was pressed onto the parchment to make a lithographic copy. Ca. 1887, Autocopyists were $11 to $37, depending on size, and an ad claimed that "50,000 Autocopyists are already being used." Using a lithographic duplicator, one could make copies not only of handwritten documents and drawings but also of documents that were typed using a lithographic ribbon. Nevertheless, the market for these lithographic duplicators was limited because stencil duplicators and hektographs were superior for most office applications, the exception being in reproduction of drawings. An 1887 review of the Columbia No. 2 index typewriter indicates the variety of duplicating processes that were available: "In writing [with the Columbia typewriter] on prepared paper the writing can be transferred to a lithograph-stone, from which any quantity of copies may be secured. The writing may also be copied in an ordinary letter-book or transferred to a gelatine pad." (The Office, July 1887, p. 130) In 1932, the Addressograph-Multigraph Corp. introduced the Multilith printing process (1932 Annual Report), "a simple, revolutionary process of lithography which brings, to large and small users alike, the advantages of office lithographic reproduction." The sale of Multilith machines began in 1933. (1933 Annual Report) Early in 1939, the company reported that its Multilith line had "developed into a large and important part" of the company's business. (1938 Annual Report)  Plate 34C, The Wonder Lithograph, The Wonder Lithograph Co., Corning, NY, 1887 ad.

Multigraph Printing Duplicators Form letters were more likely to be read if they were individually addressed

and were, or appeared to be, typewritten, rather than produced using a stencil

duplicator or conventional printing press. The first commercially successful

machine to produce form letters that appeared to be typewritten was the Gammeter

Multigraph, which was introduced by American Multigraph Co. in 1902. The next

machine that produced such form letters with a distinct technology was the

Hooven Automatic Typewriter, which is discussed in this Museum's exhibit on Special-Purpose Office Typewriters. A

third technology that was used to produce such form letters was embodied in the

Addressing Multigraph and the Addressograph Dupligraph. In 1907, ads claimed that Multigraphs could produce 3,000 to 6,000 letters

per hour, depending on the skill of the operator. A Multigraph used by students

is pictured in the 1911 catalog of Hesser Business College, Manchester, NH.

Plate 36, Multigraph Printer No. 40, American Multigraph Co.  Plate 36A, Multigraph Typesetter No. 59 Plate 36B, Multigraph Printer (left) and Typesetter, 1916. 1915 Price for these two machines was $200. (System, Jan. 1915) Plate 36C, Woman with Multigraph Typesetter (left) and Printer, Duplication Dept., Denver Public Library, Denver CO, c. 1930s. Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, X-27483  Plate 36D, Multigraph, 1923  Plate 36E, Multigraph System, 1930 ad  Plate 36F, Multigraph Set-O-Type Model 99, 1932 ad The Printograph, which was introduced in 1907/08 and

still advertised in 1913, was similar but used a flat bed rather than a drum.

Other brands with flat beds that were sold during 1908-14 include the

Writerpress, the Planotype, the Niagara Multiple Typewriter, and the Universal

Polygraph. The Planotype was $100. The Niagara was available in models priced

at $90 and $145. The Universal was $100 but the price was eventually reduced to

$50. These machines used typewriter type that was arranged by hand in a holder.

They printed through a ribbon. |

Plate 38, Printograph, 1909  Plate 38A, Writerpress  Plate 38B, Writerpress, Writerpress Co., Buffalo, NY, 1908 ad. Image shows one woman operating the press and two others composing form letters by manually arranging type in a holder.

|

In 1924, the American Manicopy Typewriter Co. attempted to raise capital to produce the Manicopy Machine. The machine was based on US patents No. 1,301,146 and No 1,452,945 awarded to Chester A. Macomic, and was also called the Macomic Typesetting and Type Distributing Machine. A photograph of one of these machines is immediately to the left. "Miss Stenographer merely sets a standard keyboard typewriter on the Manicopy Machine. She places a piece of paper in the typewriter and starts to write. Plungers underneath the typewriter keys are depressed every time a key on the typewriter is struck, thus setting the type on the Manicopy. When she has completed writing the letter or circular, she turns a lever and the type which has been set on the line bars are conveyed automatically to the printing surface where the desired number of copies is printed automatically. After the job is completed, these line bars are returned to their original positions automatically by turning a lever, and by turning another lever the type is instantly and automatically returned to its proper position without the type being touched by hand." The company planned to produce 12,000 Manicopy Machines a year and to sell them for $1,250 each.. We have found no evidence that the company raised the capital necessary to go into commercial production. In 1924, American Multigraph introduced the Multigraph Keyboard Compotype, a complicated machine that enabled the operator to set Multigraph type by working at a typewriter-style keyboard. The Compotype composed the body of the form letter by stamping characters on strip aluminum and automatically assembling the strips of type--a line at a time--on a flexible sheet metal blanket. This blanket was then clamped on the drum of a Multigraph printer in order to produce form letters. The Compotype also produced address plates.  Plate 38C, Maanicopy Machine, 1924 prospectus

|

In 1927, American Multigraph introduced the Addressing Multigraph, which

"typewrites a letter, signs a signature, fills in the address and typewrites the

envelope, all at a single revolution of the drum." The Addressing Multigraph

used plates made with the Keyboard Compotype. Like Hollerith tabulating

machines, Addressing Multigraphs were leased rather than sold to users. In 1947, Multigraph machines were sold to offices for a wide range of

duplicating purposes, e.g., production of large quantities of blank business

forms and promotional materials. (Addressograph-Multigraph, 1947 Annual

Report)  Plate 38D, Multigraph System, 1930 ad  Plate 38E, Multigraph Set-O-Type Model 99, 1932 ad

| Photocopying Machines Used to Copy Existing Documents

|

Photocopying

Machines One result of the difficulty of copying incoming documents is that offices maintained central files. Everett Alldredge of the National Archives in Washington, DC, stated: "Before the Xerox era [which began in 1960], every government agency had one central filing system. When anybody needed information he went to that central file. But today, with the copying of documents made so easy, many a government executive prefers to maintain files in his own office." (John H. Dessauer, My Years with Xerox, 1971, p. xiv) . |

|

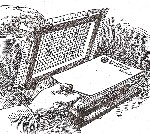

The Blue

Process The blue process was a contact printing technology: photosensitive paper was placed in contact with the document that was being copied. A clerk began by using paper and chemicals (potassium ferrocyanide and ferric citrate) to prepare photosensitive paper. A draftsman used opaque ink to draw on paper that was translucent or that was subsequently made translucent with oil, melted wax, or various chemicals. Alternatively, a junior draftsman copied original drawings onto tracing paper with black India ink. The clerk then put a sheet of photosensitive paper in the tray of a blue printing frame, covered this with the translucent original or India ink tracing, and covered this with a heavy glass plate that pressed the papers together. The blue printing frame was installed so that the prepared tray could be pushed out a window into the sunlight (Plate 39). The clerk exposed the tray for anywhere from several minutes to an hour, depending on the brightness of the day, and used chemicals to fix the print. The result, a blue print, had a blue background where the photosensitive paper had been exposed to light and white lines where the paper had not been exposed. The blue process was time consuming and impractical for duplication of typical office documents, however, even though by 1881 commercially prepared photosensitive paper for use in the blue process was available. Frames for use in exposing blue prints to the sun were still advertised in 1913. However, after the development of electric illumination and installation of electrical distribution systems, blueprint machines were developed that operated indoors with carbon arc lamps. On these machines, the frames that held the photosensitive paper and the original were in a vertical rather than horizontal plane. For an early photograph of one of these machines, click on the link to B. L. Makepeace, Inc., scroll down, and then click on the link to first blueprinting machines in New England. See also Plate 39A to the right. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, a number of contact printing processes similar to the blue process but employing different chemicals were used to produce prints that differed in appearance, e.g., colored lines on white backgrounds.

|

|

Camera-Based Photocopying Machines The

Rectigraph Co. introduced camera-based photocopying machines in 1906 or 1907,

and the Photostat Corp. (an affiliate of Eastman Kodak) did so at some point

during 1907-11. Rectigraph and Photostat machines (Plates 40-42) combined

a large camera and a developing machine and used sensitized paper furnished in

350-foot rolls. "The prints are made direct on sensitized paper, no negative,

plate or film intervening. The usual exposure is ten seconds. After the exposure

has been made the paper is cut off and carried underneath the exposure chamber

to the developing bath, where it remains for 35 seconds, and is then drawn into

a fixing bath. While one print is being developed or fixed, another exposure can

be made. When the copies are removed from the fixing bath, they are allowed to

dry by exposure to the air, or may be run through a drying machine. The first

print taken from the original is a 'black' print; the whites in the original are

black and the blacks, white. (Plate 43) A white 'positive' print of the

original is made by rephotographing the black print. As many positives as

required may be made by continuing to photograph the black print." (The

American Digest of Business Machines, 1924.) Du Pont Co. files include black

prints of graphs dating from 1909, and the company acquired a Photostat machine

in 1912. (Yates, p. 248, n. 81) A System, Sept. 1913 ad stated "20 Photostats used by the U.S. Government." In 1911, a Photostat machine was $500. (Yates, p. 54.) In 1924, Photostat machines were $650 to $1,050, depending on maximum print size and attachments. The cost of materials per print was $.06 for an 11.5" x 14" print. Similar Rectigraph machines were $500 to $850.

Plate 40, Photostat Machine, 1918 photo Image coming Plate 40A, Photostat Machine, 1924 Photo coming [Leffingwell 1926, p. 401] Plate 40B, Photostat Machine, 1926.  Plate 40C, Photocopying Machine at Acacia Mutual Life Insurance Co. Photograph by Theodor Horydczak (c. 1890-1971) ID: thc 5a39875, Repro. No: LC-H814-T-1578-067. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.  Plate 41, Photostat Camera Courtesy of Good Old Things  Plate 42, Rectigraph with Copy Board, Rectigraph Co., Rochester, NY Plate 43, Photostat black print Library of Congress, American Memory, An American Time Capsule

| Reflex Copying Machines While invented in 1896, reflex copying technologies became significant during the 1920s and 1930s. Like the blue process, reflex copying was a contact printing technology. In reflex copying, a sheet of photosensitive paper was placed face down on an original, and the back of the photosensitive paper was exposed to light. Light reflected from the original exposed the emulsion on the front of the photosensitive paper. In the 1930s, Remington Rand sold Dexigraph reflex copying machines. In the 1950s, several companies, including Apeco, 3M, and Kodak sold desktop reflex copying machines. Typically, an original to be copied was placed face-up. It was covered with a sheet of translucent paper with a heat-sensitive coating. This is the sheet on which the copy would appear. Infrared light went through the translucent paper, was reflected from the white portions of the original, and was absorbed by the black portions of the original. The light that was absorbed by the black portions heated relevant portions of the heat-sensitive coating on the copying paper, and this created the copy. This technology had numerous problems, according to Owen. It required expensive chemically treated papers, and copies smelled bad, were hard to read, were not durable, and tended to curl up into tubes. (David Owen, "Making Copies," Smithsonian, Aug. 2004, pp. 91-97.) For a history of Apeco and the photocopying industry of which it was a part, see the Harvard Business School discussion.

Plate 44, Apeco Auto-Stat, 1954 ad Plate 44A, 3M Thermo-Fax, 1956 aa  Plate 44B, Kodak Verifax, 1958 ad

|

Electrostatic Photocopying Machines: Xerography The

first experimental electrostatic photocopy was made by Chester F. Carlson in

1938. Carlson patented the xerography process, which was further developed by

the Battelle Memorial Institute and the Haloid Co. The first commercially

successful machine to use the technology was Haloid's Model A Copier,

which was introduced in 1950 (Dessauer). The Model A was not a plain paper

copying machine. It was widely used to make paper master plates for offset

duplicating with machines made by the Addressograph-Multigraph Co. and others.

The Haloid Co. was renamed Haloid-Xerox Inc. in 1958. The first plain paper

office copying machine, the Xerox 914, was introduced in early 1960

(Dessauer). The Xerox 914 produced 400 copies an hour. After 1960, sales of

the 914 increased rapidly and Xerox copying machines quickly became important in

offices. In 1963, the company introduced its first desktop plain paper copier,

the Xerox 813. In 1965, the company introduced the Xerox 2400, a

large machine that produced 2400 copies an hour. (For a history, see Dessauer

1971 and Owen 2004.)

Plates 45 through 45C: Courtesy of Xerox Corporation.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Exhibit Notes

(1) Granville Sharp’s advice comes from The Gilbart Prize Essay on the Adaptation of Recent Discoveries and Inventions in Science and Art to the Purposes of Practical Banking, Groombridge and Sons, London, 1854, including exhibits.

(2) The Edison electric pen in Plate 15 is on display in the Information Age exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History in Washington, DC. The Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, also has an electric pen. The Science Museum in London has a number of early copying machines, including a Watt portable copying press, a Trypograph, and a Cyclostyle.

(3) W. B. Proudfoot, The Origin of Stencil Duplicating, Hutchinson, London, 1972, and B. Rhodes & W. W. Streeter, Before Photocopying: The Art and History of Mechanical Copying, 1780-1938, Oak Knoll Press, 1999, are excellent illustrated histories of early copying technologies. J. S. Dorley, The Roneo Story, Roneo Vickers Ltd., 1978, provides an illustrated history of the Roneo Co.

(4) T. A. Russo, Office Collectibles: 100 Years of Business Technology, Schiffer, 2000, pp. 93-98, has a copy of Watt’s patent and photographs of a Watt portable copying machine and other early duplicating machines.

W.

A. Kelsey & Co. began to market small lever presses in 1872 and

continued to sell them for over a century. The online Briar

Press Museum has photographs of early Kelsey presses (

W.

A. Kelsey & Co. began to market small lever presses in 1872 and

continued to sell them for over a century. The online Briar

Press Museum has photographs of early Kelsey presses (