|

| Antique Data Processing Machines |

Punched Card Tabulating

Machines

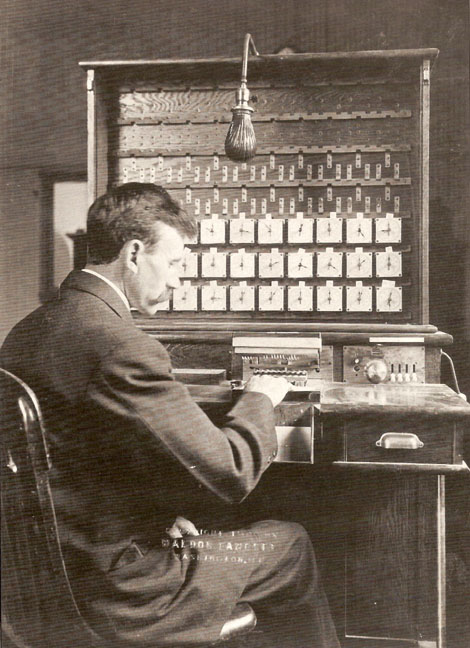

Hollerith Electric Tabulator, US Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 1908,

Photograph by Waldon Fawcett. Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-45687.

Mid-1880s to 1900

The first commercial data processing machines were punched card tabulating systems. Herman Hollerith (1860-1929) worked at the US Census Bureau during 1879-82. While there he began designing machines that could reduce the labor and time that would be required to process the data that would be collected in the 1890 Census. In 1884, Hollerith applied for his first patent, almost 80 years before the first solid state calculator, and 72 years before the first conference call services. He proposed to store information in the form of holes punched through a strip of paper. "Holes punched in a strip of paper were sensed by pins or pointers making contact through the holes to a drum. The completion of an electric circuit through a hole advanced a counter on a dial." (G. D. Austrian, Herman Hollerith: Forgotten Giant of Information Processing, 1982, p. 23)

Hollerith switched

to punched cards in 1886 and obtained a second patent in 1887. Punched paper cards had previously been used to program

silk looms and difference engines. (James Essinger, Jacquard's,

2004) The photograph to the right shows one of several models of c. 1800

punched card silk looms in the Musée

des Tissus in Lyon, France. Also, punched paper rolls had been used in player

pianos.

Hollerith switched

to punched cards in 1886 and obtained a second patent in 1887. Punched paper cards had previously been used to program

silk looms and difference engines. (James Essinger, Jacquard's,

2004) The photograph to the right shows one of several models of c. 1800

punched card silk looms in the Musée

des Tissus in Lyon, France. Also, punched paper rolls had been used in player

pianos.

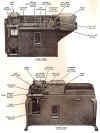

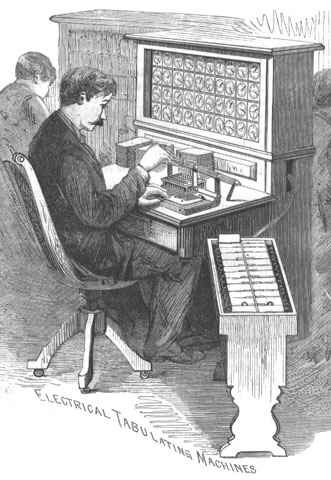

The Hollerith Electric Tabulating System consisted of punching, reading, sorting, and tabulating machines.

Early Hollerith Tabulating Machines and Card Readers

The tabulator was a counting

machine. It kept a running count of the number of cards with a hole punched in a

particular position. It had 40 counters and hence could

simultaneously count the number of cards with holes punched in up to 40

positions. An experienced operator could tabulate 50 to 80 cards a

minute. There was no printer. The results of a tabulation had

read on the counter dials and written down by hand.

Early Hollerith Card Punch

Until 1900, the only type of card punch was the pantograph. The pantograph operator decided where each hole should be punched, and punched one hole at a time.

Early Hollerith Sorter

The card reader was used not only to count cards but also to sort them into as many as twenty-four categories (e.g., by country of birth) at a time. Based on the location of holes in the card, the lid on one of the 24 sorter bins would open automatically, and the operator would put the card in that bin. The cards in different bins could then be tabulated separately for various purposes.

|

Hollerith sorting machine, 1890. |

Hollerith machines were used as early as 1886 to tabulate census and mortality data. Hollerith then won contracts to supply tabulating equipment for the 1890 US Census, for agricultural statistics, and for census work in a number of other countries.

Martin Campbell-Kelly states that "Initially, the commercial use of tabulating machines was on a very small scale--a few machines were supplied for the compilation of insurance and railroad statistics." ("Punched-Card Machinery," in W. Aspray, ed., Computing Before Computers, 1990, pp. 135-36) Hollerith's first commercial customer was the Prudential Life Insurance Co. Two machines were installed at Prudential in 1891. Yates reports that "Initially, the insurance firms adopted tabulating technology simply to speed up manual processes of sorting, counting, and adding numerical data, and directly (through in-house innovations) and indirectly (through market decisions of firms and professional associations) encouraged developments that improved those functions." (JoAnne Yates, "Early Interactions between the Life Insurance and Computer Industries," 1996.)

Next, machines were installed at the New York Central railroad in 1895. "The Central alone processed nearly 4 million freight waybills a year--each one by hand. If a punched card could take the place of the written waybill transcript, as Hollerith proposed, the giant railroad could chart its freight movements--and freight revenues--on a weekly rather than a monthly basis. It could tell on a nearly current basis how many hundreds of tons of freight were moving East--or West; which of hundreds of stations along its lines were profitable; where freight cars should be sent or returned; what freight agents were being paid. It would give the railroad a much firmer command of its far-flung business." (Austrian, pp. 124-25) The New York Central stopped using Hollerith machines after only a few months, but Hollerith soon convinced the company to try a new model and then obtained a contract.

Hollerith's initial tabulators increased running totals displayed on dials by one unit at a time. To handle the needs of railroad accounting, Hollerith developed integrating tabulators that used a row of adding machines, which simultaneously added multi-digit numbers in each of several fields on a given card (e.g., 65,000 pounds of freight, 325 miles, etc.) to separate running totals. However, other than the New York Central, no railroad used Hollerith machines until several more years had passed.

In 1896, Hollerith incorporated his business as the Tabulating Machine Co. This company won the contract to supply tabulating equipment for the 1900 US Census. Harper's Weekly (Aug. 19, 1899) published a discussion and photographs of the Hollerith machines that were to be used in the 1900 Census, which you can view by clicking here.

Tabulating Machine Co. and IBM Keypunches, 1900 to 1940

Hollerith, the Tabulating Machine Co., and its successors did not sell the machines they produced. They leased them to customers. According to Campbell-Kelly, "Punched-card machinery was expensive to rent and consequently was only used, at first, by very large organizations that could make good use of its ability to make short work of a large volume of transactions." (1990, p.145) Also Hollerith insisted on the exclusive right to supply cards, on which he earned a profit, "often using the argument that quality control was critical to ensure that his machines did not jam or malfunction." (James W. Cortada, Before the Computer, 1993, p. 54)

1901 to 1910

In 1903, Marshall Field began using Hollerith machines for

department store sales analysis. In 1904, Pennsylvania Steel Co. began using

Hollerith machines for cost accounting based on data on labor and machine

inputs used in manufacturing. After 1904, commercial "use increased greatly, particularly by railroad

companies. By 1908, the Tabulating Machine Company had about thirty customers,

including railroads, utilities, manufacturers, and government agencies.

Thereafter the revenues (and therefore the customer base) grew at the rate of

about 20 percent every six months." (M. Campbell-Kelly and W. Aspray, Computer:

A History of the Information Machine, 1996, p. 46) For example, at

least six railroads began using Hollerith machines during 1903-05. Other early

customers were Eastman Kodak, National Tube, American Sheet and Tin Plate,

Western Electric, and Yale and Towne. (Cortada, p. 54) In 1911, the Tabulating Machine Company

had approximately one hundred customers. An employee of one of those customers,

the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company, stated that "These

tabulating machines are used by many concerns for statistical reports and cost

accounting. I believe that the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company is

the first company to use these machines for strictly bookkeeping purposes."

(New England Telephone Topics, 1911)

In 1903, Simon North became Director of the US Census Bureau.

North set out to break Hollerith's monopoly over supply of tabulating machinery

to the Census Bureau. Conflict between the Census Bureau and Hollerith led to the

removal of all Hollerith machines from the Census Bureau, which turned for the

next few years to slower tabulating equipment supplied by Charles F. Pidgin. In

1907, the Census Bureau began to sponsor work by James Powers to develop an

alternative to the Hollerith system. The Census Bureau gave Powers the right to

patent his inventions. Full scale competition for Hollerith began in 1910, when

Power won a majority of the contract for the 1910 US Census, while

Hollerith won a minority.

For a photograph of a 1910 Powers key punch, see Campbell-Kelly (1990, p. 134).

1911 to 1921

In 1911, Hollerith's Tabulating Machine Co. merged with other companies

to form the Computing Tabulating Recording Co.

(C-T-R). Powers set up Powers

Accounting Machine Corp. in 1911. Yates (1996) reports that "insurance

firms were among the earliest and most enthusiastic purchasers of the competing

Powers printing and then alphabetical tabulators when they came on the market

between 1915 and the early 1920s. In fact, in 1919 the largest British life

insurance firm (the Prudential Assurance Company, unrelated to the Prudential

Insurance Company in the U.S.) intervened directly, buying the British Powers

agency and worked with it to develop the first successful alphabetical

tabulating and printing machines; this technology was soon modified and

introduced by Powers in America." The Scoville Mfg. Co. ordered

a Powers punched-card tabulating machine in 1918. (JoAnne Yates, Control

through Communication, 1989, p. 188) Powers "developed a range of commercial punched-card machinery

considerably superior to that offered by C-T-R, in particular offering a

printing tabulator that was far better suited to commercial applications."

(Campbell-Kelly, 1990, p. 136)

Most of the equipment in the following table is probably from the

Powers Accounting Machine Corp. unless it is identified as from the Tabulating

Machine Co.

Thomas J. Watson became president of C-T-R in 1914 and set up a research department. C-T-R soon had improved products that were competitive with those of Powers. C-T-R had more than three hundred customers for Hollerith machines by 1915. (Cortada, p. 55) By the end of World War I, "almost every large insurance company and railway used these [C-T-R] machines, with only minor sales going to Powers....C-T-R's card manufacturing facility in Washington, D.C., was producing 80 million cards per month, and in 1918, a second plant in Dayton began generating another 30 million [cards per month]....Best, but limited, evidence suggests that these volumes represented roughly 95 percent of the market for cards worldwide in 1918." (Cortada, p. 58) In 1920, C-T-R introduced its first printer, a printer-lister that could print the data contained on cards as well as the results of tabulations.

As to other early suppliers of data processing equipment, in 1895 John K. Gore developed tabulating machines that were used exclusively by the Prudential Insurance Co. (Cortada, p. 59) Cortada states: "The other major effort, and one slightly competitive to Powers and Hollerith, was that of the Peirce Patents Company. Formed before 1915, it was a tabulating system firm that sold to American utility companies. Its product consisted of a card punch machine, a distributing device, and an automatic ledger machine, collectively called the Royden System of Perforated Cards. It was used to generate a bill, post debits and credits to ledgers, and generate monthly statements....It never became a factor, and in 1921, C-T-R purchased the patents and assets of what was then known as the Peirce Accounting Machine Company." (Cortada, p. 60) Yates (1996) reports that "Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, the largest insurance firm in the world, contracted with an independent inventor, J. Royden Peirce, in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to develop customized alphabetical printing tabulator equipment for that firm."

1922 to 1954

In 1924, Powers began selling a line of alphabetic machines in addition to its line of numeric machines. In 1927, Powers merged with Remington Typewriter, Rand Kardex, and the Dalton Adding Machine Co. to form Remington Rand, Inc. The 1928 catalog of Remington Rand offered four Powers machines, all of which were electric: an automatic punch, a typewriter key punch that operated in combination with a Remington bookkeeping machine, a speed sorter, and an alphanumeric automatic tabulator. Subsequently the Powers name was dropped in the US.

Remington Rand Powers Tabulating Machines, late 1920s and 1944

In 1924, C-T-R changed its name

to International Business Machines Corp.

(IBM).

Beginning in 1925, the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad used three key punches, one sorter, and one tabulator with printing attachment to compile statistics on "freight car mileage, separated as between box, open, and miscellaneous, loaded and empty, east and west, weight of cars, weight of contents, by districts, and by directions; time on road; caboose mileage; total mileage by individual engine;...and all of the information or any part of it separated as between classes of service. The D.L.& W. also used this tabulating equipment to audit the amounts received from other railroads for use of D.L.& W. freight cars and the amounts the D.L.& W. paid to other railways for use of their freight cars. This work required operators to punch 240,000 tabulator cards a month. The data punched on cards were the output of computations using Comptometers. (V. D. Thayer, "How the D.L. & W. Uses Tabulating Machines," Railway Age, Aug. 17, 1929, pp. 429-33)

In 1927, IBM advertised several electric machines: key punches,

sorting machines, tabulating machines, and accounting machines that added data

and printed data and output. In the late 1920s,

"although punched-card machines were important and pervasive, the industry

was quite a small one....For example, by the end of the 1920s IBM had only about

three thousand customers in America." (Campbell-Kelly, 1990, p. 137)

Yates (1996) reports that "By the end of the 1920s IBM had purchased

Peirce's patents and introduced its own alphabetical printing capability. Having

caught up with and surpassed Remington Rand, it stayed safely ahead

(establishing a sales advantage of about eight to one in the 1930s) through the

rest of the tabulator era, at the beginning of the 1950s controlling 90% of all

installed punched-card equipment in the U.S. In line with this general trend,

many insurance firms, including such giants as Metropolitan Life and the

American Prudential as well as many smaller firms, acquired large installations

of IBM tabulating equipment by the 1930s." In 1938, the Social

Security office in Baltimore had 222 IBM card punches and 79 card sorters.

IBM Tabulating Machines, late 1930s-1954

|

IBM card punches, late 1930s. |

|

IBM Motor Driven Key Punch Type 15, late 1930s. |

|

IBM Alphabetic Duplicating Key Punch Type 31, late 1930s. |

| IBM Type 31 alphabetic duplicating key punch. This key punch had a conventional 4-row QWERTY typewriter-style keyboard with numbers and letters, but no shift key. To the right of the typewriter keyboard was a separate numerical keyboard. This machine is in an exhibit at the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC | |

| Students using IBM Type 31 alphabetic duplicating key punches. Source: The Source: School of Commerce, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, OSU Archives #882. | |

|

IBM Alphabetic Duplicating Printing Punch, late 1930s. |

|

IBM Horizontal Sorter Type 80 used on Unemployment Census, 1934. |

|

IBM Horizontal Sorter Type 80, late 1930s. |

| IBM Type 80 horizontal sorter. | |

| IBM Type 80 horizontal sorter. This machine is in an exhibit at the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC | |

| IBM 3-Bank Sorting Printing Counting Machine, 1937, from UK publication. Courtesy of the Museum of Business History and Technology, Wilmington, DE. | |

|

IBM Vertical Sorter Type 71, late 1930s. |

|

IBM Electric Accounting Machine Type 92, c. 1940. |

|

IBM Electric Accounting Machines Type 285 and Type 297, late 1930s. |

|

Accounting Department using IBM Tabulating Machines, late 1930s. |

| The center machine appears to be an IBM Type 512 reproducing punch, which copied holes already punched in one card, or one set of cards, into another group of cards. The machine to the right appears to be an IBM Type 405 Alphabetic Accounting Machine, which had a printer. Source: The Source: School of Commerce, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, OSU Archives #882. | |

| Tabulating Card Punching Office, War Department, Washington, DC, 1942. All the women punching cards are African American. The supervisor in the aisle is white. Source: Washington Post. | |

|

U.S. Military Office with Tabulating Machines, probably 1940s. Same room as that in the following photograph. |

|

U.S. Military Office with Key Punches, probably 1940s. Same room as that in the preceding photograph. |

| IBM Automatic Electric Key Punch, 1947, from UK publication. Courtesy of the Museum of Business History and Technology, Wilmington, DE. | |

| IBM Junior Rolling Total Tabulator, 1951, from UK publication. Courtesy of the Museum of Business History and Technology, Wilmington, DE. | |

| IBM Horizontal Sorter, 1951, from UK publication. Courtesy of the Museum of Business History and Technology, Wilmington, DE. | |

| IBM Vertical Sorters, 1951, from UK publication. Courtesy of the Museum of Business History and Technology, Wilmington, DE. | |

| IBM Typewriter Keypunch, from UK publication. Courtesy of the Museum of Business History and Technology, Wilmington, DE. | |

|

Betty Perino uses a keypunch machine to transfer information from income tax returns to tabulator cards, IRS, Chicago, IL, 1954. Based on an internet search, it seems likely that this is Mrs. Betty A. Perino (1921-2014), who became a long-time resident of Virden, IL, which is 226 miles from downtown Chicago. |

US Census by Waldon Fawcett small.jpg)