Early Office Museum

Antique Special Purpose Typewriters

This Museum gallery covers the following special purpose typewriters: shorthand typewriters, the Edison mimeograph typewriter, book typewriters, billing typewriters, combination typewriter-adding or bookkeeping machines, automatic typewriters, Japanese language typewriters, braille typewriters, encryption machines, and music typewriters. (MBHT) designates images that are courtesy of the Museum of Business History and Technology.

|

|

Shorthand Typewriters Adler (1997, p. 43) reports that the first stenographic typewriter was invented in 1827. He also reports (p. 37) that another stenograph machine that printed on paper tape was introduced by Michela in 1862 and was manufactured in France and Italy into the 1880s. The Stenograph(patented 1879-82,

introduced 1882) was a shorthand typewriter invented and produced by Miles M. Bartholomew.

The machine printed a code of dashes lengthwise in different positions on a

3/8" paper strip. For example, a single dash near one edge of the tape

represented the letter d. A single dash a little farther from the same

edge represented the letter n. The sequence d n stood for the word done. "All

the letters can be made either with the right hand or the left. The

4 finger pieces on the left of the keyboard are duplicates of those on the

right, and make the same marks on the paper. Those on the left are

operated by the fingers of the left hand, and those on the right by the

fingers of the right hand. The straight key [located between the two

sets of 4 keys] is operated by either thumb. ... [The] machine [is] so

made that the complete alphabet is produced with either hand and the hands

used alternately in writing, as the feet are in walking. ... In the autumn

of 1881 the inventor began using it in his work as a court stenographer,

but no extended effort was made to introduce it until the autumn of

1883,... At this time about 80 instruments had been sold." (Appletons'

Annual Cyclopaedia 1890, 1891, p. 816) During 1883-86 the Stenograph was $40.

The Universal Stenotype Co. (which soon thereafter became the Stenograph Co.) introduced the Stenotype in 1912. The machine used 16 letters to spell words phonetically with one word per line on a roll of paper 2 3/8" wide. The machine was initially successful but the company folded in 1918-19. In the late 1920s another entity purchased the rights to make Stenotypes, and it made machines under the Stenotype and Stenograph names for many years. Marco Thorne reports that the Stenotype was not widely used in business offices, because it was too large and heavy for the typical stenographer to carry into an executive's office to record a letter. The Stenotype was used primarily in court rooms and elsewhere to produce transcripts. (ETCetera, No. 39, June 1997) |

|

|

|

Edison Mimeograph Typewriter Index typewriters did not play a significant role in offices because they were slow. As a result, our principal discussion of index machines is included on a separate web page. One index typewriter was designed specifically for office use, however: the short-lived 1894 Edison Mimeograph Typewriter. This typewriter was designed to type stencils used in the Edison Mimeograph duplicating system, but it could be used for other typing as well. This typewriter was invented and produced not by Thomas A. Edison but by A. B.. Dick, which also produced and marketed the Edison Mimeograph. The type was on the tops of vertical type-bars (three of which are identified by blue highlights in the photograph to the right). To select a letter, the operator rotated a disk with letters on it located on the bottom of the machine. This caused a vertical rod (identified by the red dot) to rotate, and this in turn caused the circle of type-bars to rotate so that the selected type-bar came into position. The operator then pressed a lever (yellow dot) to activate a hammer (green dot) that struck the lower end of the type-bar that carried the selected letter. The plunger-like type-bar moved up and the type struck the underside of the platen. The typewriter was therefore a blind-writer; the operator had to lift the hinged carriage in order to see her work. (See photograph to the right and image to the left of machines with the carriages up.) There

were three models at $22-$25. The machine had a short commercial

life because it was

slow. |

For spectacular photographs of another Edison Mimeograph |

|

|

Book Typewriters Book typewriters typed on bound books that lay flat when opened, including bookkeeping ledgers, books used to record deeds, and other books used to maintain government and business records. Book typewriters were also used to type letters while simultaneously printing carbon copies in a bound copy book. The first practical book typewriter was the Elliott Book Typewriter produced by the Elliott & Hatch Book Typewriter Co., New York, NY (1897). While the book remained stationary, the typewriter moved on rails as the operator typed. When keys were pushed, the type-bars struck downward. Elliott book typewriters were advertised during 1901-02. A 1902 advertisement claimed that the machine could do everything any writing machine could do. The advertisement claimed the Elliott was particularly suitable for typing manifolds (forms with alternating sheets of paper and carbon paper) used for ordering and billing, and that it could make twenty good copies at a time. An attachment could be used to feed paper and carbon paper into the machine automatically. At about this time, a mechanism was added that enabled the operator to add columns of numbers. According to an observer, "The great power of manifolding which the firm platen yields, permits of many copies being made simultaneously, so that on receipt of an order a single operation will permit of an acknowledgment being typed, and at the same time all other necessary forms for manufacturing, packing, shipping, invoices, etc." (Mares, 1909, p. 168) In 1898 the Elliott Book Typewriter was $175. The Fisher Book-Typewriter Co.,

Cincinnati, OH, developed a new book

typewriter with a number of advantages, including typing that was visible to the operator.

This was marketed as the Fisher Book Typewriter and Billing Typewriter as of 1901.

(See image below left.)

|

|

Fisher Billing Typewriter, Fisher Book-Typewriter Co., Cleveland, OH, 1901 ad |

The mechanization of book-keeping began in the very early 1900s. In 1905, Chas. E. Sweetland stated that "there are many firms now using the book typewriter or billing machine and producing the bill, the charge, the delivery slip, and the salesman's record, and any other forms necessary for the business, in one writing." (Anti-Confusion Business Methods, St. Louis, 1905, p. 52) In 1906, Erwin William Thompson published Book-keeping by Machinery, which began with the statement that "a field practically unexplored" is "the actual performance of book-keeping and auditing by machinery." (p. 1) Thompson observed that "Small offices...employing from one to three men...generally cannot better their condition by the use of much book-keeping machinery." (p. 7) But Thompson accurately argued that for larger offices use of machinery for book-keeping would be efficient. At about the same time that offices adopted machines for book-keeping, offices adopted standardized forms that could be completed on book-keeping machines and filed in loose-leaf binders or files. | . |

|

|

Billing Typewriters Elliott-Fisher typewriters were advertised for billing and

-- with the addition of adding modules -- for adding and billing by the

very early 1900s. See illustrations to left. The Oliver Typewriter Co. produced a Way-Billing Typewriter, which was an Oliver No. 2 with a tabulator attachment. The Virtual Typewriter Museum has an illustration. Because the Oliver No. 2 was introduced in 1897, this Way-Billing Typewriter may have been introduced shortly after that. The Smith Premier Tabulating and Billing Machine was advertised in 1899, and the Remington Billing Typewriter (top right) was introduced in 1903. These billing typewriters had a tabulator mechanism for form and tabular work located on the rear of the machine. The image top right shows a row of tabulator keys (mounted horizontally) along the front of the base of a Remington Billing Typewriter, which was a modified Remington No. 6 upstrike. The number and location of the tabulator keys changed over time on successive Remington models that had tabulators. Remington marketed its No. 7 with a tabulator, and in 1908 Remington began to market its No. 11 front-strike typewriter with a tabulator. The tabulator keys on the No. 11 were located above the regular keyboard.

|

|

|

|

Combination Typewriter-Adding Machines ~Howieson ~ Elliot-Fisher ~ Remington ~ Smith Premier ~ Moon-Hopkins ~ Ellis ~ NCR ~ Underwood ~ From 1904 through the 1920s, a number of companies sold combination typewriting-adding machines for use in accounting departments. These machines were variously called writing-adding, typewriter-adding, typewriter billing, and typewriter bookkeeping machines, as well as adding and subtracting typewriters. Some of these were blind-writers. They were used to do the adding and typing required for tasks such as preparation of invoices.. In 1904, the Arithmograph Co. and the Fay-Sholes Co. advertised the Arithmograph,

"an adding device mounted upon a typewriter, at present the Fay-Sholes

Typewriter. The Arithmograph, which was patented in 1902-03 by John T.

Howieson, "consists of a series of adding wheels, and their driving

mechanism,...so connected to the numeral keys as to add numbers" when

the operator engages the mechanism. When writing invoices, it will tabulate them. It does the work

of a typewriter and adding machine with the single operation of

typewriting." The Arithmograph together with a Fay-Sholes

typewriter was $200. |

|

|

|

By 1904, the Elliott-Fisher

Co. produced Billing and Adding Machines that combined the ability to

type on a flat surface with the ability to add columns of numbers. (See

illustration top left.) While the book typewriters discussed above were

often used to type on the pages of bound books, these billing machines

were generally used to type on standardized loose-leaf forms. One reason

they were used is that they were able to make more carbon copies than the

typical alternative billing machine. A Billing Machine alone was

$190 ($200 in 1906); an Adding

Attachment with two registers was an additional $190 ($220 in 1906). In 1908, Elliott-Fisher advertised

"Forty-Seven thousand and some odd more are doing their work the

Elliott-Fisher Way," which implies that the company had sold at least

47,000 book and bookkeeping typewriters. In 1910, the company claimed that

"95% of the machines used for writing and adding are Elliott-Fisher

machines. 5% only are typewriters with attachments or adding

machines with typewriter attachments." In 1921, Elliott-Fisher advertised its Universal

Accounting Machine for accounting work on statement and ledger forms. The

largest capacity Universal Accounting Machine could carry out addition in

23 columns at one time. In 1923, Elliott-Fisher stated that the

Snellenburg and Lord & Taylor department stores used 40 and 30 of its

Universal Accounting Machines, respectively, to handle customer accounts,

accounts payable, and accounts receivable.

|

|

|

|

Beginning in 1909, the Remington Typewriter Co. advertised its No. 11 with a Wahl Adding and Subtracting Attachment, or Wahl Register, in addition to a tabulator. This machine was marketed for uses that required writing combined with adding and subtracting in vertical columns on the same page. Uses included filling out order forms and ledger sheets and preparing bills and statements. The Smith Premier No. 10-A Adding and Subtracting Typewriter, which also had a Wahl Totalizer, was similar. In 1916, Remington introduced the Remington Accounting Machine (Wahl Mechanism), which looked like the No. 23 pictured to the right. In 1927 Remington marketed its Model 23 Bookkeeping Machine for applications requiring horizontal as well as vertical adding. The latter had an automatic electric carriage return and line spacer. In 1925, Remington advertised the decimal calculator attachment shown at the left for its No. 11 typewriter. The operation of these machines has been described as

follows: "The usual method of accomplishing addition and subtraction

is by means of registers called totalizers, which are attached to a rack

on the front of the machine. These totalizers are movable from column to

column. As many totalizers may be used as there are columns to be added or

subtracted, up to about thirty. Computation is performed by depression of

the regular numeral keys and the amounts appear in the register." (American Technical Society, Practical Business Administration,

1930, Vol. 9, "Office Equipment," p. 26.) |

|

|

|

In 1911, Burroughs Adding Machine Co. was developing typewriter-adding machines. Two drawings are shown at the left. Moon-Hopkins Billing Machine Co., named for its president John C. Moon and vice president Hubert Hopkins, marketed a typewriter-calculating machine from 1909 until 1921, when it was acquired by Burroughs Adding Machine Co. Burroughs continued to market the machine until at least 1951 (by which time the plate glass on the sides had been replaced by sheet metal and the name Moon-Hopkins had apparently been dropped). The front part of this machine was an upstrike typewriter; the rear was a direct multiplication calculating machine. The Moon-Hopkins had a conventional 4-row keyboard for the typewriter. In front of this was a 2-row keyboard with two sets of keys numbered from 0 to 9 for the calculating machine. The machine was able to type 20 carbon copies of an invoice or other document.

In 1911, electric motors

were added to the Moon-Hopkins, and models were priced at $500-$750.

One model was $750 in 1916. In 1924, different models were priced at $650 to $1000, plus $50 each for

additional registers for the calculating machine. Kidwell (2000, p. 17)

states that, if serial numbers are to be trusted, Moon-Hopkins sold a total of 3,226 machines by June

1921. |

|

|

|

Ellis Adding-Typewriter Co.

sold typewriter-adding machines from 1911 until 1929, when the company was

purchased by the National Cash Register Co. The

1909 Remington

machine described above was a typewriter with an adding/subtracting attachment. The Ellis

was an adding machine designed to print on ledger cards; it was supplied

both with and without the addition of a typewriter keyboard. A

merchant could have a ledger card for each customer and use an Ellis

machine to update a customer's credit balance each time a purchase was

made or a payment was received. For a photograph of an Ellis Adding-Typewriter, see Kidwell

(2000), Figure 10. Ellis

machines were sold by NCR as National Accounting Machines, National Typewriter Bookkeeping Machines

and NCR Accounting Machines from 1930 until at least 1962. At

one time, NCR produced at least 13 different models for various types of

accounting and bookkeeping applications.  Woman in Office with NCR National Accounting Machine, Burroughs adding machine, and checkwriter

Woman in Office with NCR National Accounting Machine, Burroughs adding machine, and checkwriter

|

|

|

|

Underwood

Typewriter Co. also

produced combination typewriting-adding machines by 1910. In 1911, an ad stated that "the Underwood Computing Machine meets the long felt want

for a machine that will write names and descriptions and list amounts in

as many columns as may be required, and automatically add or subtract the

amounts in all columns both vertically and cross-wise. The computing

mechanism is attached to the figure keys (of the standard typewriter

keyboard), which do computing automatically as the keys are struck and the

figures are imprinted on the paper." The computing mechanism was

electric. The prices of the four models of computing mechanisms (not

including the price of the necessary typewriter with decimal tabulator)

were $200 to $275 in 1911. Underwood bookkeeping machines were still advertised in 1923. Subsequently, Underwood and adding machine manufacturer Sundstrand apparently merged, and the company offered Underwood Sundstrand Accounting Machines.  Underwood Computing Machine Model B with Underwood No. 5 Typewriter, 1911 ad

Underwood Computing Machine Model B with Underwood No. 5 Typewriter, 1911 ad

|

|

Secretary with Bookkeeping Machine, mid-1900s |

. | . |

|

|

Automatic

Typewriters Automatic typewriters were designed to type form letters. Early automatic typewriters were similar to player pianos. A person typed a letter on a perforator that punched holes in a wide paper fanfold or roll or, later, a narrower paper tape. The paper fanfold, roll or tape was then put in a machine that controlled a typewriter. The typewriter would type a form letter over and over again, stopping at predetermined points so that an operator could insert individualized material such as names, dates, quantities and prices. The

Hooven Automatic Typewriter, which was

electric, was introduced in 1911. "The Hooven is an automatic,

electrically driven mechanism which operates a standard Underwood

typewriter mounted upon it. The operation of the typewriter during the

typing of the letter follows exactly the [same] mechanical movements as

when the machine is operated by a typist. These mechanical movements are

actuated and controlled by a perforated strip of record paper (similar to

a perforated roll used on a player piano), running through the automatic

mechanism of the machine. The record paper is cut on an auxiliary machined

called the 'Perforator'. "The normal typewriting speed is 130 words per minute. The usual procedure in larger institutions is to have one attendant for a battery of three or four machines, inserting paper, making fill-ins and removing paper successively from each machine. Fill-ins of addresses and other changes throughout the letter are typed manually by the attendant." (The American Digest of Business Machines, 1924, pp. 246-47, which listed the Automatic Device complete with Underwood No. 5 typewriter at $650 and the Perforator at $75.) The manufacturer claimed that a typist with four Hoovens could do the work of 12 to 16 typists. Hooven systems were still marketed in 1937 by the Hooven Automatic Typewriter Corp. |

|

Auto-Typist with IBM electric typewriter. Three rows of buttons to the left of the typewriter were used to select paragraphs to be included in a customized form letter.  Auto-Typist Model 5020, American Automatic Typewriter Co,, Chicago, IL, 1951 image |

The Auto-Typist, which was introduced in 1927, was produced in the 1930s by the Schultz Player Piano Co. and later by the American Automatic Typewriter Co. The Auto-Typist consisted of two machines. A perforator was used to punch a wide paper roll. The paper roll was read by another machine housed in a special typewriter desk. The latter machine controlled the keys of a standard manual or electric typewriter through a system of pneumatic bellows, hoses, and valves. The operator could customize a form letter by pushing numbered buttons on a control panel to select paragraphs to be included. Auto-Typists were still marketed in 1951 and in use during the 1960s. The Aerotype was similar to the Auto-Typist.

|

|

|

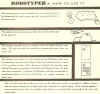

Robotyper. Right unit made paper rolls. Form letters were produced by a typewriter resting on the left unit. |

Other automatic typewriters included the Robotyper, which was introduced in 1935, and the Flexowriter, which was introduced in the early 1940s. The Robotyper was pneumatic and used paper rolls. According to a 1951 ad by the Robotyper Corp., Hendersonville, NC, "Operating four Robotypers, one girl can produce from 600 to 800 perfectly typed, personalized letters in an 8-hour day." (See photo top right.) Robotyper introduced the Carlson Selector (see photo bottom right) in 1951 for answering letters using paragraph stored on punched cards. "The executive determines from a list of predetermined paragraphs" the ones that will properly answer each letter. The operator could also use the Carlson as a conventional manual typewriter. |

|

|

|

The Flexowriter used paper tape and was also used as an input-output device on computers in the 1950s.

|

|

|

|

Composing Machines Machines based on the Hammond office typewriter design were sold under the Vari-Typer (later VariTyper) name from 1927 until 1977-78. Vari-Typers were not ordinary typewriters but composing machines that made professional looking camera-ready masters for offset (photo-lithographic) duplication. As on the Hammond, one could easily change the type-shuttles on the Vari-Typer to type in different fonts and languages. The Vari-Typer added right justification (1937), variable letter spacing (1947), and variable line spacing (1951). As of 1951, Vari-Typer machines were produced by Ralph C Coxhead Corp, Newark, NJ. As of 1960, the VariTyper Corp. was a subsidiary of the Addressograph-Multigraph Corp. (We discuss Addressograph and Multigraph machines in our exhibits on Mail Room Machines and Copying Machines, respectively.) The range of products with the VariTyper brand name had expanded to include office machines that look nothing like the earlier typewriter-like Vari-Typer machines. (Addressograph-Multigraph, 1960 Annual Report, illustrations) The 1967 Annual Report of the Addressograph-Multigraph Corp., which also owned the Addressograph, Multigraph, and Multilith brands, states:

The 1967 Annual Report further states that "VariTyper

is pursuing aggressively a wide range of direct impression typography and

photo-typesetting products to serve better the needs for type

composition." VariTyper ceased making the typewriter-like

direct impression machines in 1977-78. "With the manufacture of

the last strike-on composing machine during fiscal 1978, A-M's transition

to microprocessor based phototypesetting technology is complete."

(Addressograph-Multigraph, 1978 Annual Report) The 1985 Annual

Report of AM International (successor to Addressograph-Multigraph) states

that its VariTyper division supplied "computer-based

phototypesetters, terminals, composition systems." |

Coxhead Vari-Typer Composing Machine (MBHT) Coxhead Vari-Typer Composing Machine, 1951 brochure (MBHT) |

|

Chinese and Japanese Language Typewriters The first typewriter with Chinese characters was produced around 1911-14. Nippon Typewriter Co. began producing typewriters with Chinese and Japanese characters in 1917. A typical Japanese typewriter of this type has a flat bed with the most commonly used 2,400 to 3,000 Japanese characters, well short of the total of around 50,000 that exist. (Thomas A. Russo, Office Collectibles: 100 Years of Business Technology, Schiffer, 2000, p. 161; ETCetera No. 73, Mar. 2006, p. 7) A successor company, Nippon Remington Rand Kaisha, was producing similar machines in the 1970s. To use the typewriter, paper is wrapped around the cylindrical rubber platen, which moves on rollers over the bed of type. The operator uses a level to control an arm that picks up a piece of metal type from the bed, presses it against the paper, and returns it to its niche. While the machine is complicated, because of the shorthand character of Japanese writing, the Japanese language typewriter is nearly equal to an English language typewriter in speed for recording thoughts.

|

For a

photograph of a Nippon Typewriter, see Thomas A. Russo, Mechanical

Typewriters, p. 166. |

|

|

Braille Typewriters For information on braille typewriters and numerous photographs, click on the following link to the American Printing House for the Blind Callahan Museum.

|

|

Code Machine |

Encryption Machines | . |

Columbia Music Typewriter, 1886 ad Melotyp Music Typewriter Vistomatic Musicwriter |

Music Typewriters ~ Columbia ~ Melotyp ~ Keaton ~ The illustration to the left shows the simple Columbia Music Typewriter, which sold for $10 in 1886. "This is the invention of Charles Spiro [who also invented the Columbia Typewriter and the Bar-Lock Typewriter], and was patented Dec. 1, 1885. The music written by this instrument is the exact equal of a printed sheet, and can be adapted, by a special device, to print in the words of a song by the use of an additional type wheel. It is 4 1/2 inches in length, 2 inches in width, and 2 1/2 inches in height, and weighs 1/2 a pount. There is a disk, a handle, and a base. The disk contains on its periphery the requisite characters,.... The disks are 3, 1 containing the notes, 1 for inserting accidentals, and 1 for signatures and barring." (Appletons' Annual Cyclopaedia 1890, 1891, p. 817) The Melotyp music typewriter was made in Germany. It won a grand prize at the 1937 International Exhibition in Paris. According to a member of the family, only 10 of these typewriters were made. Robert H. Keaton received a patent

for a 14 key downstrike music typewriter in 1936 and for the 33 key

downstrike Keaton Music Typewriter shown to the right in 1953. Like the Elliott-Fisher book

typewriter, the Keaton types on a sheet of paper lying on the flat platen

under the machine. The machine sold during the mid-1950s for $225 (D. Rehr, ETCetera, No. 25, Dec. 1993)

and for $255 and $355 (MBHT) |

Keaton Music Typewriter   Two Keaton Music Typewriter brochure images (MBHT) |