|

| Filing Equipment |

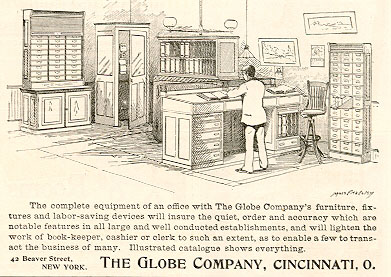

Antique Filing Systems

1896

The Principles of Indexing and Filing, a 1932 text, provides the following retrospective on filing equipment: "Filing is the disposing of papers in such a manner that they may be found easily. The early methods of storing correspondence cannot be called filing, as we use the term today. In former times, letters were often folded, with the name of the correspondent or subject on the outside, and stored in pigeon-holes in desks or cabinets. Spike or spindle files were also used. Papers of various kinds were hooked on a spike placed on the wall or on a desk. When the spike or spindle became full, the papers were removed, tied together, and stored. The box file was an improvement. In the box file papers were laid flat between sheets of stiff paper, each sheet having a tab. A letter or a division of the alphabet was printed on the tab. A filing cabinet with shallow drawers or trays was later used instead of many different box files. Each drawer or tray was labeled with a letter or division of the alphabet, and the papers were laid flat in the drawer. This method of filing often made it necessary to lift up many papers before the one desired could be found. The old methods of filing papers flat often led to an endless search and the waste of valuable time. The flat file, therefore, has been discontinued for general correspondence filing. The result was the development of the various systems of vertical filing in use at present. The bellows file was an improvement on the box file when only a few papers had to be filed. Papers were placed upright in the bellows file and were more easily located. Papers in a modernly equipped office are put in folders and placed behind guides in a vertical filing cabinet." According to another statement, "The old method of flat filing proved to be incapable of economic expansion, as the indexes are in a fixed position and the drawers are small. Unnecessary space is consumed in cabinet divisions, and superfluous and at the same time inadequate indexes use up half the filing space. The Vertical Filing System permits of expansion and contraction without limit and without necessitating any troublesome rearrangement." (The Hoskins Company Catalog, c. 1910)

For a recent, more detailed historical

account of the development and early use of filing equipment, see JoAnne Yates, Control

through Communication, 1989,

Chap. 2. Describing the filing system used by General Henry Du Pont, head of the

Du Pont black powder manufacturing company from 1850 to 1889, Yates (p. 206)

states that "General Henry's desk had sufficient pigeonholes to hold folded

and annotated papers for the previous year, and a large pigeonhole cabinet held

those from several more years. Correspondence that was older still was

retired to the attic in boxes."

Click on the links at the top of this page to go to The Early Office Museum's

three exhibits on early filing equipment: Desks; Filing Cabinets &

Safes; and Small Files and Filing Devices.

We have little information on the filing equipment that was in use in offices

before 1850. We suspect that long before 1850 papers were stored on shelves and

in drawers, pigeonholes, and boxes. According to Yates p. 28, citing to a 1926

source), "Through the middle of the [nineteenth] century, the pigeonhole

[in desks and cabinets] was the primary storage device for such [loose incoming]

correspondence, sometimes supplemented by a desk spindle on which papers could

be impaled." In

addition, outgoing letters were copied into bound books by hand and, after 1780

(but to only a limited extent prior to the mid-nineteenth century),

using letter copying presses. Data were kept in ledgers. And important papers

and ledgers were stored in safes.

In the exhibits, we list the date of the earliest advertisement that we have found for each type of product, as well as the date of the earliest patent that we have found (provided that we know that the item covered by the patent was in fact marketed). Further research will undoubtedly enable us to identify earlier advertisements and patents.